Sodium Graphite Reactors

By Nick Touran, Ph.D., P.E., 2023-03-13 , Reading time: 6 minutes

In the 1950s, hordes of nuclear reactor designers were rushing to find out which combination of coolant, moderator, and fuel types would be the most economical for commercial power production. Along the way, someone came up with the idea of using sodium metal coolant with graphite moderator. It’s a sodium-cooled slow reactor (as opposed to the more common sodium-cooled fast reactor). The idea here was to capture the following benefits:

-

Sodium metal coolant can be brought to higher temperature than high-pressure water, allowing higher thermal efficiency (more heat can be converted to electricity when the heat is higher temperature). Thus, you can get more revenue for the same amount of nuclear heat and equipment, and therefore be more economical.

-

Sodium metal coolant remains at low pressure even at these high temperature. Thus, the thickness of pipes and protection equipment to deal with high-pressure leaks in water-cooled reactors can be reduced/eliminated.

-

Graphite moderator allows reactors to work with very little fissile mass and enrichment. This allows operation with natural or low-enriched uranium, as opposed to sodium-cooled fast reactors, which require ~12% or higher enrichment (or fissile concentration) to start up and maintain a neutron chain reaction.

The first two benefits are shared with the far more well-known sodium-cooled fast reactor (SFR) design, but the last one is what’s so special about SGRs. When high-fissile fuel such as HALEU or HEU or Plutonium is a little hard to come by, SGRs shine. This condition exists in any country that is not aggressively reprocessing its spent nuclear fuel.

1963 Atomic Energy Commission video about Hallam, digitized from the National Archives thanks to Nebraska Public Power District. See our announcement of the world re-premier of this film here.

The first vocal champion of the SGR design was Chauncey Starr, best known for later founding the non-profit, Electrical Power Research Institute (EPRI). While at Atomics International, he edited an entire book about SGRs that was released globally at the 2nd Atoms for Peace convention in 1958 and can be read in full today for free.

As was typical in the history of reactor development, we developed, built, and operated two SGRs:

- A reactor experiment: Sodium Reactor Experiment (SRE) 29 miles NW of Los Angeles, California.

- A power prototype: Hallam Nuclear Power Facility (HNPF) 18 miles SE of Lincoln, Nebraska.

As was common in the pioneering days of nuclear, these reactors were not without issues. SRE had a coolant issue that led to melted fuel, and Hallam had issues with the moderator cans leaking, allowing sodium to contact the graphite and cause swelling. The vendor, Atomics International, figured out solutions to these issues but did not make enough progress to convince Consumers Public Power District (the utility partner) to purchase Hallam at that time. Thus, as was the deal in the AEC’s Power Demonstration Reactor Program (PDRP), the AEC would decommission the plant.

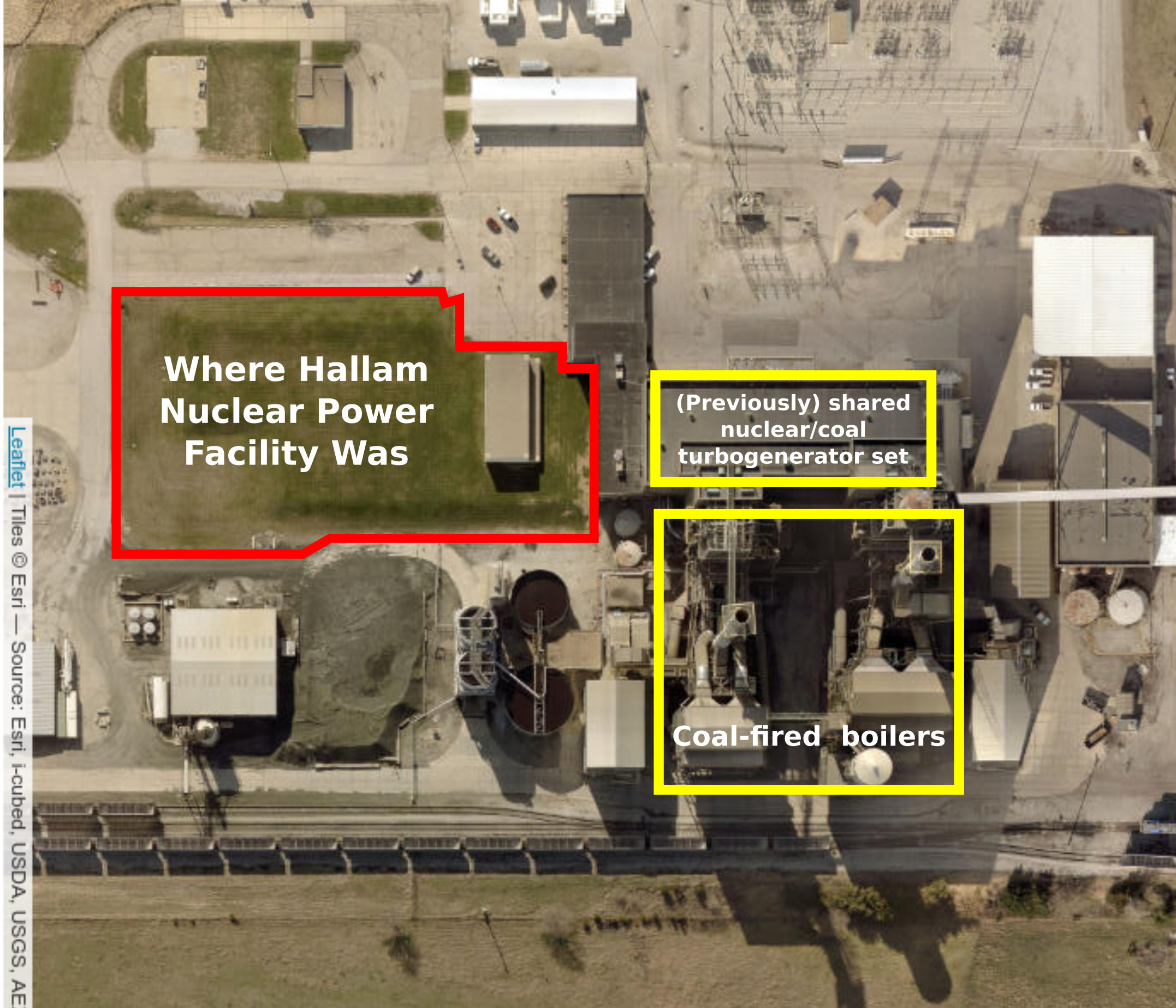

Consumers entered into the experimental reactor program knowing they needed the power for their customers one way or another. Because sodium-cooled reactors can generate steam of the exact same quality as a coal plant, they decided to build a coal-fired plant right next to the HNPF and hook it up to the exact same turbine-generator set. When the nuclear plant would be down, the coal plant could fill the gap, and the customers could have reliable power. The plant as a whole was (and still is) called Sheldon Power Station.

As far as we’re aware, this was the only time in history that a nuclear and coal plant have fed steam into a shared turbine.

Overhead view of Sheldon Power Station, showing the outline of where the Hallam sodium-graphite reactor was and the existing coal and (previously-shared) turbine facilities. Typical water-cooled reactors can’t make steam hot enough for this.

The shared nuclear/coal turbine/generator itself (from AEC)

Some Technical SGR Papers

General

- Weisner, A sodium-graphite reactor steam-electric station for 75 megawatts net generation, 1955

- Starr, Sodium Graphite Reactors, 1958

- Proceedings of the SRE-OMRE forum, 1958

- Connolly, Self-sustaining plutonium recycle in sodium graphite reactors

- Shaw, Control elements for sodium graphite reactors, 1959

- Hayward, Sodium graphite reactor materials survey, 1959

- Connolly, Fuel programming for sodium graphite reactors, 1959

- Hayward, Radiation behavior of metallic fuels for sodium graphite reactors, 1959

- Koenig, Properties of ceramic and cermet fuels for sodium graphite reactors, 1960

- Reed, Evaluation of calandria, thimble, and canned-moderator concepts for sodium graphite reactors, 1960

- Cappel, Transient behavior of an advanced sodium graphite reactor, 1961

- Rood, 1000-Mwe SGR: core optimization studies, NA-SR-9501, 1964

- Lee, Process development for bonding zircaloy 2 cladding to graphite moderator

- Quarterly Technical Progress Report AEC Unclassified Programs, NAA-SR-11900, Jan 1964

- More…

SRE

- Sodium graphite reactor quarterly progress report, July 1954

- Glasgow, Sodium graphite reactor quarterly progress report, NAA-SR-1760, July 1956

- Proceedings of the SRE-OMRE forum, 1956

- Sodium graphite reactor quarterly progress report, Nov 1956

- Annual Technical Report AEC Unclassified Programs, NAA-SR-2400, January 1957

- Cambell, Low-power physics experiments on the sodium reactor experiment

- Hayward, SRE experimental fuel program, 1959

- Miller, Development of the SRE thimble-type control rods: Mark I and II, NAA-SR-2011, 1959

- Phillips, Development of the SRE Mark I safety rod, NA-SR-2008, 1959

- Dryer, SRE Reactor Fuel Handling Equipment, NAA-SR-5599, 1960

- Freede, SRE core recovery program, 1961

- Weaver, Sodium Reactor Experiment reactivity history program, NA-SR-10010, 1964

- Pellet, Core II physics tests on the sodium reactor experiment, NA-SR-9510, 1964

- Keaten, Nuclear parameters of the SRE core II, 1964

- Dietz, SRE Mark II Fuel Handling Machine, NAA-SR-10817, 1965

Hallam

- Dunsmore, Development of temperature protective circuits for the HNPF fuel channel exit, 1961

- Doyas, Hallam critical experiment, 1961

- Mahlmeister, Engineering and constructing the Hallam Nuclear Power Facility reactor structure, 1962

- Aronchick, Nuclear startup experiments for HNPF, NA-SR-10078, 1964

- Kapsic, Experimental testing of core component handling equipment and handling techniques for Hallam Nuclear Power Facility, NA-SR-7785, 1964

Large Sodium Graphite Reactor (LSGR)

LSGR was the next step after Hallam I guess.

See Also

- Sodium Reactor Experiment Construction

- Hallam SGR photos

- ANS Nuclear Cafe – Hallam Nuclear Station on 1960’s TV!

- Sheldon Power Station

- Hallam Nuclear Power Facility

- Sodium Reactor Experiment

- Atomic Energy in Nebraska 1 Sheldon Station Construction – related video also digitized by Nebraska Public Power District

- Atomic Energy in Nebraska 2 Sheldon Station Construction – related video also digitized by Nebraska Public Power District, including an amazing shot of the reactor vessel after it rolled off the truck into a corn field (without significant damage).

- Operational Experience, Hallam – A 1964 video summarizing the operating experience. Footage is basically the same as the 1963 video posted above, but condensed.

- Our reactor history page’s SGR section